|

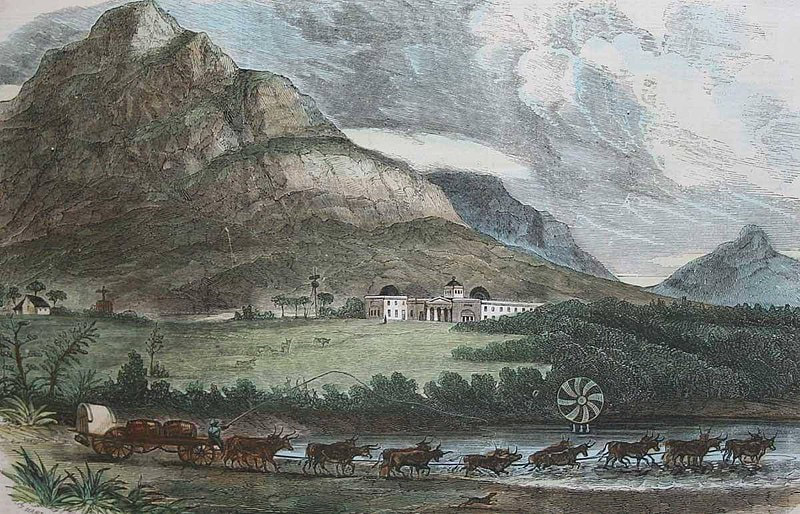

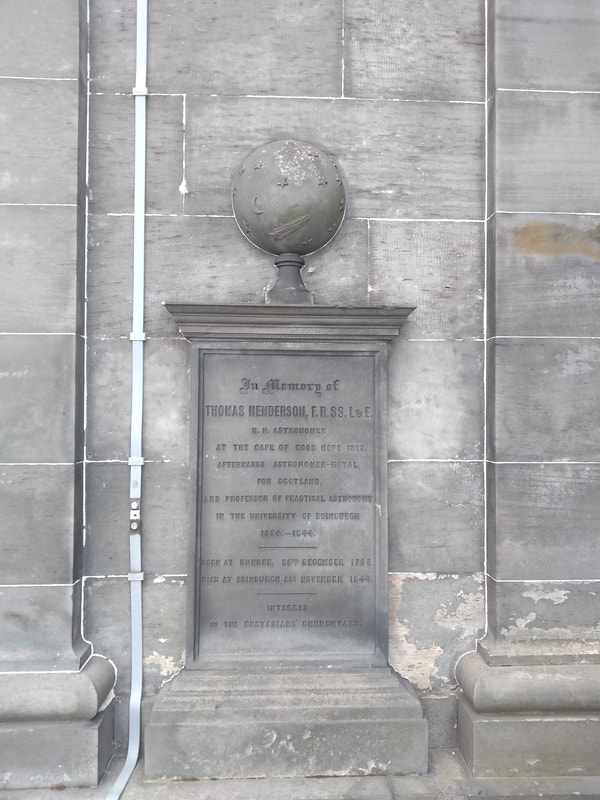

How many people, even those with a scientific interest, are aware that Edinburgh is associated with one of the holy grails of astronomy? Thomas Henderson's House, Hillhead Crescent, Edinburgh The story is one that begins many thousand miles from Edinburgh, at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa. It is where the Scottish astronomer, Thomas Henderson, was appointed H.M. Royal Astronomer in the year 1831. Born in Dundee in 1798, he began his career as a lawyer’s clerk, before his passion for astronomy eventually led to his appointment. Although complaining of the difficult working conditions (from defect telescopes, to having to check for snakes under his bed), he made a substantial number of astronomical observations during his time at the Cape. After just over a year, however, he decided he had endured enough of the “dismal swamp” as he called it, his frail health being affected by the local climate. His predecessor had died from scarlet fever and was actually buried in the observatory grounds, so Henderson returned to Scotland probably trying to avoid a similar fate. Portrait of Thomas Henderson During his last month in South Africa, intrigued by the observation made by another astronomer, Manuel Johnson based on the south Atlantic island of St Helena, that the star alpha Centauri (technically a star system) which is the closest to our solar system, exhibited a substantial change in its position relative to other stars, he focused his work on this discovery. What he was primarily interested in was the detection of a parallax for alpha Centauri, the apparent change in position of an object when viewed from different vantage points. As our planet moves around the sun, the view we get of a star changes ever so slightly during the year as it appears to move relative to its background. The fact that alpha Centauri seemed to exhibit a measurable movement, suggested that a parallax effect might be at play. Importantly, by obtaining the parallax of an object, it is possible to estimate its distance (the closer the object is to the observer, the greater the parallax). As stars are at an immense distance from us, their parallax is extremely small and is not detectable to the naked eye. Ever since antiquity, astronomers had been trying, without success, to detect this subtle effect. Nineteenth century telescopes however, had reached the technological level required for parallax detection and astronomers were caught up in a tantalising race to reach this holy grail of astronomy. The Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope Even so, for reasons that are still not entirely clear, Henderson apparently saw no urgency in further analysing his observations of alpha Centauri and instead applied himself to more routine tasks after returning to his native country. Had he possessed the confidence to formally publish his results, his claim to fame would have been much greater. The announcement from the German astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel that he had managed to measure the parallax and therefore the distance of another star, 61 Cyg, finally motivated Henderson to analyse his results in more detail in late 1838. In January 1839, more than six years after his observations had been made, he published his results which were read at a meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). His initial parallax estimations determined the distance of alpha Centauri to be at 3.25 light years (one light year being the distance travelled by light in a vacuum in one year) when in fact it is 4.37 light years. He later improved his estimate to 3.57 light years, after obtaining better quality results from his successor (and good friend) at Cape Town, astronomer Thomas Maclear. Thomas Henderson Commemoration Plaque, Calton Hill, Edinburgh Although the accuracy of the results may not be great by modern standards, Henderson had gauged the distance of a star, a feat of historical significance. Incredibly, he had achieved this without fully believing or realising it himself, and so came second to formally publishing a result. It is because of this that it was Bessel and not Henderson who was awarded the Gold Medal from the RAS and who is generally acknowledged as the winner of the scientific race. In fact, within just a few months, three astronomers had published their star parallax results (the third one being the German-Russian astronomer Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve). So important was the feat that when John Herschel, the president of the RAS, awarded the medal, he declared: “Gentlemen, I congratulate you and myself that we have lived to see the great and hitherto impassable barrier to our excursions into the sidereal universe—that barrier against which we have chafed so long and so vainly - almost simultaneously overleaped at three different points. It is the greatest and most glorious triumph which practical astronomy has ever witnessed”. So how is this fascinating story of science history connected to Edinburgh's Calton Hill that overlooks the eastern end of Princess Street (Edinburgh’s main shopping street)? After returning to Scotland Henderson was appointed the first ever Scottish Astronomer Royal and Professor of Astronomy at Edinburgh university. He worked at the Calton Hill observatory for ten years, recording over 60,000 observations of star positions. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1832, the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1834, and the Royal Society of London in 1840. Henderson died from heart disease at his home, in 1844. Two years before his death he met Bessel in Edinburgh in what he described as one of the highlights of his life. A plaque outside the main observatory building commemorates him and the house in which he spent his final years is also signposted at the foot of the hill. Although little known and difficult to imagine, a scientific quest which started in antiquity, was concluded in this very part of the city of Edinburgh. The Calton Hill Observatory The Calton Hill Observatory has many other stories that will certainly fascinate you. To learn more about those and about several other sites and aspects of the rich scientific history of Edinburgh & Glasgow, check out the Scientific Secrets of Edinburgh & Glasgow!

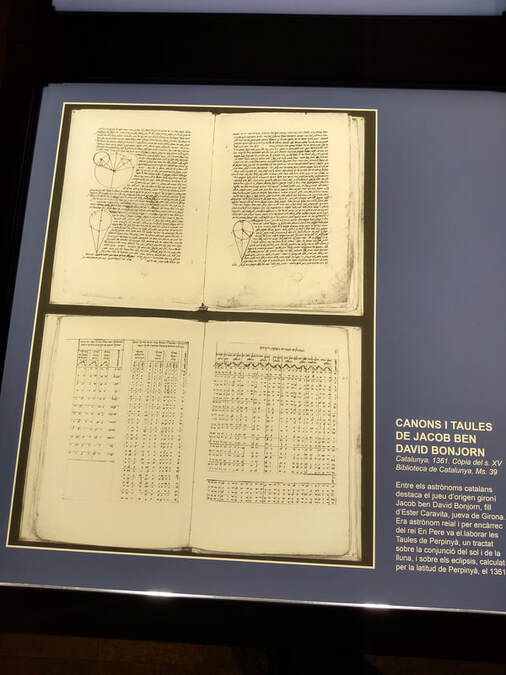

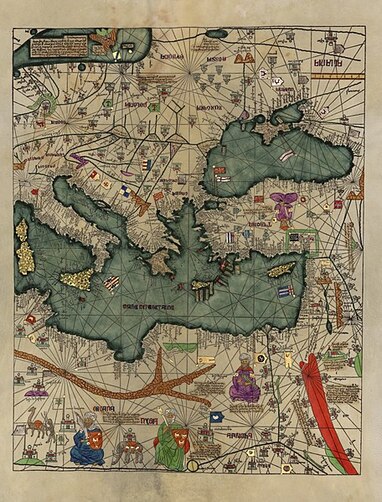

Although not known to many, Jewish medieval scholars made significant scientific contributions, primarily in the fields of astronomy and cartography. Catalonia and the city of Girona in particular, was one of the centres of Jewish culture during those times. Important figures such as the famous medieval Jewish scholar Moses ben Nahman commonly known as Nachmanides, lived in this part of the world. In fact, one could present a whole list of influential figures who grew up or flourished in this city. Courtyard of Museum of Jewish History, Girona In this post, I will focus on Jacob ben David Bonjorn, born in Girona at around 1330 and who was one of the leading figures of astronomy in the 14th century. Working for the King of Aragon Peter "the Ceremonious" at the town of Perpignan (a short distance from Girona and now part of France), he produced a set of important astronomical tables extensively used by astronomers after him. The tables (actually based on those of another Jewish astronomer, Levi ben Gerson, who lived in Orange in southern France in the 14th century) attempted to deal with one of the most complex problems of astronomy at the time: the calculation of the timing of true syzygies. This is when the moon, sun and the Earth lie on the same line, or put more simply, it is the occurrence of new or full moons. Bonjorn’s tables provided a list of all such events for the period from 1361 to 1391. Importantly, from the astronomical data presented, the details of lunar and solar eclipses could be deduced. Bonjorn also incorporated a method by which it was possible to use the tables for predictions beyond 1391. The importance of his work is highlighted by the fact that it has survived in many manuscripts in Hebrew, Latin, Catalan, and Greek, and was used extensively by astronomers until the 15th century. The Astronomical Tables in the Museum of Jewish History Worth noting apart from the scientific achievements of our astronomer, is an episode from Bonjorn’s family life concerning his parents, which caused a major stir at the time. His mother Ester was the daughter of Astruc Caravida, a powerful Jew of illustrious lineage. As was common then, her parents arranged her marriage and the chosen husband was David Bonjorn de Barri, who (as his son later became) was a famous astronomer based in Perpignan. The marriage was not a happy one, as Bonjorn de Barri mistreated his wife who eventually demanded a divorce. When her husband refused it, she targeted his most vulnerable point: Ester got hold of her husband’s books and tools and refused to return them unless she got her way. Her tactics paid off and after going back to Girona, she was the eventual winner of a long legal battle succeeding in having her dowry returned to her. If you are interested in medieval Jewish astronomy and Jewish culture in general, you will thoroughly enjoy a visit to the Museum of Jewish History located in Girona’s beautifully preserved old Jewish Quarter. Exhibits of scientific interest include a reproduction of the famous Catalan Atlas (the original is held in the French National Library, Paris). This was a “map of the known world” created in 1373 by two Majorcan Jews, Cresques Abraham and his son Jehuda who were commissioned by the Catalan monarch. It was subsequently offered as a wedding gift to the Dauphin of France and is a prime example of medieval cartography. Part of the Catalan Atlas Jewish astronomers were also renowned astrolabe makers. An astrolabe is a scientific instrument used to measure the position of celestial bodies. Several Jewish astronomers invented modifications of the instrument to improve its accuracy and reliability. You can learn more about this at the Museum of Jewish History. Astrolabe Information from Museum of Jewish History After a visit to the museum, a wander around the maze of cobbled streets of the Jewish Quarter is thoroughly recommended. Finish off at the wonderful campus buildings of Girona University, whose history goes back to 1446. To rest from the uphill walk, relax at the outside seating of the Campus Bar, a laid back cafe and bar serving cheaply priced coffee, great sandwiches, snacks and local beers. Directly opposite the old university buildings, it is an ideal place to contemplate the rich history of a truly enchanting city. Jewish Quarter Outside Seating of the Campus Bar facing the University Buildings Finally, if you can choose when to visit Girona, the most exciting time is during the Temps de Flors flower festival which takes place every May. Amazing flower decorations, real works of art, are exhibited all around the city and all museums can be visited for free. For the scientific traveller, floral exhibits with a scientific theme can also be found! The Periodic Table with Flowers Celebrating Science!

Asclepius was the ancient Greek god of medicine and healing, worshipped in many parts of ancient Greece including Athens. He was in fact a semi – god, son of divine Apollo, and the mortal Koronis from Trikala in central Greece. The descendants of Asclepius, who themselves practised medicine, were known as the Asclepiads, the most famous of which was Hippocrates of Kos, often referred to as the “father of medicine”. The rod of Asclepius, a serpent-entwined rod wielded by the god, is used as a symbol of medicine even to this day. Asclepius was worshipped in sanctuaries called “Asclepieia”, one of the most important of which was in Epidavros in the Peloponnese, where a world famous ancient theatre is also situated. Importantly, the Asclepieia did not only serve as a place of worship but also offered health care, combining the medical science of the time with a variety of religious and magical elements. A holistic type of medical care was thus offered, where particular emphasis was given to the emotional state of patients. The centres were therefore built in locations of great natural beauty. Buildings such as theatres and gymnasiums, used by patients for physical exercise and recreation, were constructed next to where physicians practised medicine. Most of the above is probably known to anyone with an interest in Greek mythology. How many of you are aware, however, that the ruins of a sanctuary to Asclepius can be found in the most unlikely of regions, thousands of miles from Greece? The city Ἐμπόριον (Greek: Ἐμπόριον, Emporion, meaning “trading place” – “market”) was founded in the 6th century BC by Greek colonists from Phocaea (an ancient Ionian Greek city). It is in present day Catalonia, Spain, a short drive from the medieval city of Girona and a 1 hour and 40 minutes’ drive from Barcelona. The colony was founded for trading purposes and the initial settlement (Palaia Polis) was followed by a second one (Neapolis) the remains of which you can visit today. Part of the Empuries Ruins Overlooking the Mediterranean Sea The ruins of Emporion (now called Empuries), lie facing the Mediterranean Sea in an exceptionally beautiful setting. There is an archaeological park and the branch of the Archaeology Museum of Catalonia in Empuries (MAC-Empuries) offer visitors an enriching experience. A visit to the Greek city and the adjacent Roman one (that was subsequently built after the Romans arrived in the 2nd century BC), can be followed by a tour through the museum. The museum contains representative objectives from the excavations that commenced about 100 years ago. Beautiful Setting of Empuries Ruins There are many interesting artefacts to observe but without doubt the most impressive one is a beautifully refurbished statue of Asclepius which was found in 1909 (see top of page). The statue is made of both Pentelic and Parian marble. It once stood in a small sanctuary dedicated to the god. A replica of the statue has been placed in the ruins so you can see Asclepius gaze towards the Mediterranean Sea, to where he originally came from. Replica of Asclepius Statue in the Ruins A trip to the Girona region is full of treats for the scientific traveller (including some great cafes and bars to digest your knowledge in) to be described in following posts! If on the other hand you are more interested in the Asclepieia and in particular the ruins of the one located on the foot of the Athens Acropolis, checkout the Scientific Secrets of Athens guide.

|

- MY SCIENCE WALKS

- SHORT BIO

-

STELLARIUM RESOURCES

- Introduction

- Astronomy and the Odyssey

- Circumference of the Earth (Eratosthenes)

- Circumference of the Earth (Posidonius)

- Distance to the Sun (Aristarchus)

- Size of the Moon (Aristarchus)

- Distance to the Moon (Hipparchus)

- Lunar eclipse of Alexander the Great

- Journey of Pytheas

- Babylonian Cycles

- Direction to Mecca

- Great Conjunction of 1166

- Medieval supernovas

- Chinese pole star

- Sidereal day of Aryabhata

- NAVIGATING WITH THE STARS

- ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM

- BOOKS & COURSES

- TRAVEL BLOG

- Contact Me

RSS Feed

RSS Feed