|

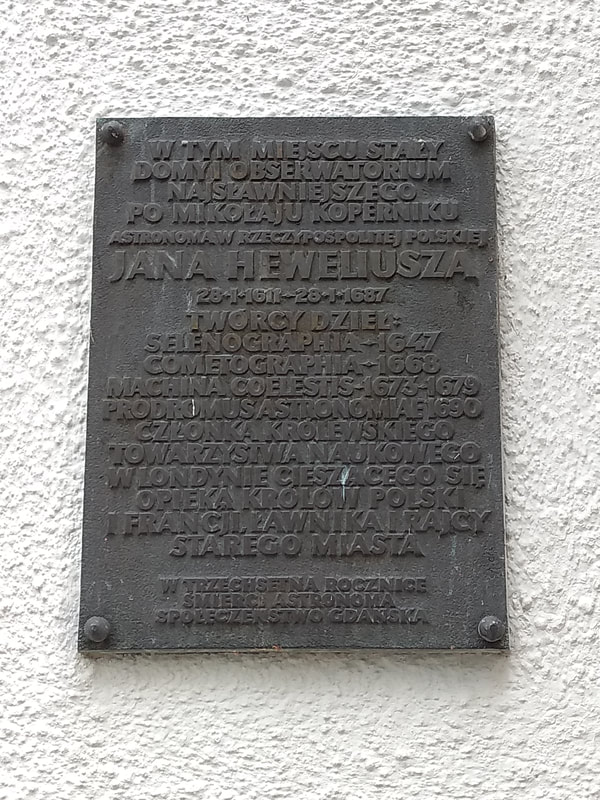

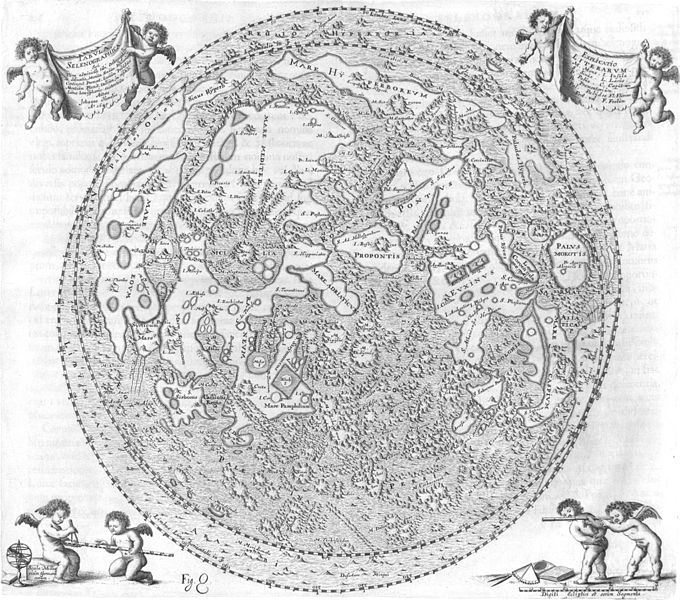

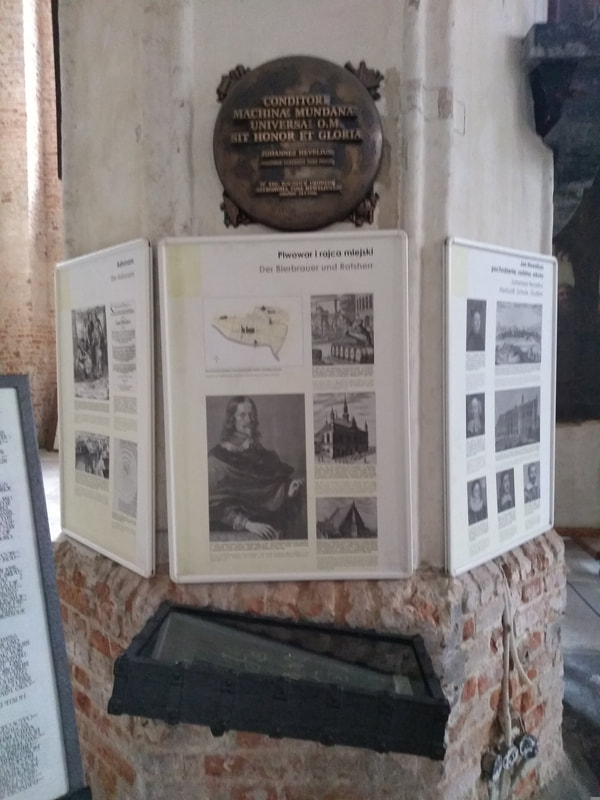

When visiting the Baltic port city of Gdansk in northern Poland, the scientific traveller is in for a treat. Remnants of famous astronomers and physicists, impressive astronomical and solar clocks, a time ball and a science museum, can all be found within the boundaries of this pretty place. What makes it even better is that all this can be enjoyed while tasting some of Poland's best cuisine together with many of its tastier beers. In fact one of its most famous residents, actually ran a 17th century brewery while at the same time defining new star constellations from the roof of his house! Johannes Hevelius Monument Johannes Hevelius (or Jan Heweliusz in Polish), was born in Gdansk (then called Danzig) in 1611, the son of wealthy brewing merchants. When he was seven years old he entered the Gymnasium at Danzig where he was latter taught mathematics by a man called Peter Krüger. Krüger was the one who planted the seeds of astronomical interest into the mind of the young Johannes. At the age of nineteen Hevelius went to the university of Leiden, in Holland. He went there not to address his astronomical enquiries but to study law, as this was seen as more useful for someone destined to take over the family brewery business. His interest in astronomy, however, never waned and he still found the time to study the mathematical sciences while in Leiden. His enthusiasm was such that he eventually left Holland in order to travel around Europe to meet the famous astronomers of the time. When he was about to seek out the great Galileo in Italy, his parents, who thought it was more important that he got engaged with the family brewing business than spending his time networking with scientists, called him back to his hometown. He returned there in 1634 and was admitted to the Brewer's Guild in 1636. A year earlier he had got married to his neighbour Katherine Rebeschke and at this point it seemed as if Hevelius was a settled family man focused on his family business. In 1639, however, two events occurred that reawakened his passion for science. A visit to his old teacher Peter Krüger and the observation of a solar eclipse were enough to thrust him back into the observation of stars and he eventually built his own observatory at the roof of his house in 1641. The instruments he constructed himself were extremely accurate for their time and he was soon making pioneering astronomical observations. Luckily for Hevelius, his wife Katherine took over most of the administrative duties of running the brewery thus freeing up some time for him to engage in his scientific activities. Plaque presenting the point where Hevelius used to live Hevelius discovered numerous comets, defined seven new star constellations still used today, studied sunspots, the planet Venus, and above all produced the most detailed study of his time of the moon; this was his famous "Selenographia" which he published in 1647. In his study of the moon, he also discovered what is known as "lunar libration in longitude". Put in simple words, this means that due to the moon's varying speed in its orbit around the Earth, we are able to view more than half of its surface over the period of one orbit. This is contrary to the popular belief that only half of the moon is visible to us. Map of the Moon from the Selenographia The new constellations that Hevelius defined and we still use today were: Lacerta (the Lizard), Leo Minor (the Lion Cub), Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs), Vulpecula (the Fox), Lynx (as it was so faint it was said that you needed to possess the eyesight of a Lynx, which Hevelius did, in order to recognise it), Sextans (an instrument he used by Hevelius for observation), Scutum (the Shield, originally called Scutum Sobiescianum in honour of Jan Sobieski III, the King of Poland and sponsor of Hevelius's work). He also defined another three constellations that astronomers do not use today. Reconstruction of the observatory of Hevelius at the Museum of Tower Clocks Hevelius's fame as an astronomer soon grew and he received visits from celebrities such as the young Edmond Halley (the later to be famous English astronomer) and the Polish king. He also became fellow the Royal Society of London, a huge honour for a non - Englishman at the time. It is interesting to note that Halley was sent to Gdansk by the Royal Society in order to settle a dispute between Hevelius and the English Physicist Robert Hooke (after which Hooke's Law in physics is named). An argument had broken out between the two men on whether Hevelius's instruments were more or less accurate that the telescopes used by Hooke and other scientists. Certificate of Hevelius for acceptance to the Royal Society It is a testimony to the remarkable personality of Hevelius that between making pioneering astronomical observations he still found the time to be involved in municipal matters of his hometown for which he served as councillor from 1651 until his death. He was also the church administrator at St. Catherine’s Church (where he is now buried) and served for a decade as a court juror. At the same time he continued to brew some of the best beer in the region and so famous was his Jopenbier beer that the (now renamed to Piwna street) was once named Jopengasse. Just as things seemed to be going well for him, however, his longtime wife Katherine died in 1662. Fate had it that a year later he married 16-year-old Elizabeth Koopman. Contrary to his first wife, Elizabeth was more interested in astronomy than in running the brewing business. She became Hevelius's scientific partner and is considered by many as the first female astronomer. Her contribution to astronomy is was of such importance that both a minor planet and a crater on Venus are named after her. Hevelius and his second wife Elizabeth taking measurements The couple continued to produce scientific work until in 1679 when a fire destroyed their observatory. Although they did manage to repair most of it (and thus observed the Great Comet in 1680), Hevelius never managed to completely overcome the shock from the disaster and he finally passed away in 1687. Hevelius's work on lunar topography is considered so important that a lunar crater has been named after him. Remnants of the great astronomer can be found all over the city of Gdansk, such as the impressive monument of him gazing at the stars (depicted on a wall opposite), close to St. Catherine's Church). Hevelius Monument gazing at the star painted wall In St Catherine's Church itself where he is buried, one can find a memorial plaque, with some information on his life. Hevelius memorial plaque At the tower of St Catherine's Church there is a small museum with tower clocks which is well worth a visit. When I was there, there was also a small exhibition of astronomical instruments that Hevelius had created together with a small reconstruction of his observatory. This was definitely an added bonus! Exhibition with some of the instruments constructed by Hevelius in the Tower Clock Museum If you are interested in visiting a science museum, on a hill overlooking the city you can find the Hevalianum, named after the great man. If you like a drink, however, the most enjoyable way to pay homage to our astonomer, is to sip the beer dedicated to him at one of the numerous excellent bars on Piwna street, (the old Jopengasse which was named after his Jopenbier beer). This is also an excellent way to digest the atmosphere of a truly great city. The Johannes beer dedicated to Hevelius There are plenty of other intriguing sites for those visiting Gdansk with an interest in science. In fact, there is another scientist that was born in the city whose name is probably more familiar to most of us than that of Hevelius. Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, was a physicist born in Gdansk (then still called Danzig), in 1686. He was the inventor of the first mercury thermometer, the first accurate thermometer of practical use. More famously, he defined the first temperature scale to be widely used, now known as the Fahrenheit Scale. His inventions were so important that he is considered a pioneer of exact temperature measurement. You can find a large thermometer dedicated as a monument to great physicist right in the centre of the Old Town. The Fahrenheit Monument Not far from the Fahrenheit Monument you can also find the house where the physicist was born. A plaque informs you of its presence. The birthplace of Fahrenheit In the Old Town, St. Mary's Church, is one of the top sites visited by tourists. For those with a scientific interest, a real delight awaits them just inside the church. The 15th century astronomical clock is one of the most impressive of its kind. It is of great beauty and complexity displaying amongst other things the phases of the moon, the position of the moon and sun in relation to the zodiac signs, and various religious dates. Unfortunately I was personally out of luck when visiting, as it was covered for maintenance but even the cover replica, you will agree, looks impressive! Cover of astronomical clock in St. Mary's Church If you are interested in time measurements you will also like the solar clock located on the exterior of St. Mary's Church. It may not be as impressive as the astronomical clock inside but originally constructed in 1553, it is certainly worth a view. Solar clock Still in the heart of the old town, on the walls of the Gothic Town Hall, another exhibit of scientific history can be found. Gdansk was a trading city and in the older days for trading to occur smoothly standards of measurement were displayed in prominent positions. At the entrance of the Gothic Town Hall are the old Gdansk standards of length: the foot (equal to 28.7 centimetres), the ell (equal to 2 feet), and the fathom (equal to 6 feet), In 1816, after the partition of Poland, the Prussians replaced these with their own, slightly longer units. Standards of measurement outside the Gothic town hall The scientific secrets of Gdansk do not end here. There are plenty more to see, including the Technical University of Gdansk, more solar clocks, a medieval crane, the birthplace of a great philosopher, the old Town Hall where Hevelius stored his beer, and even some connections to Poland's greatest astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus. I will finish this tour with a sight that those of you that have visited the Greenwich observatory, where the famous meridian lies, will be familiar with. Gdansk’s Nowy Port (New Harbor), the largest port in Poland is a short drive from the city centre. This is where you can find a historic lighthouse, constructed in 1894 (as a copy of a lighthouse in Cleveland, Ohio), which operated until 1984. The feature reminiscent of Greenwich is the restored time ball which is nowadays dropped every two hours between 12 -6 pm. Time balls were used in many world ports (including of course London) during the 19th century. At a predefined time (usually around noon), a large ball was dropped from a height for mariners to synchronise their ship clocks. This was not only important for time keeping but also for navigational purposes, as accurate timing was important for the determination of a ship's longitude. The old lighthouse and time ball This concludes my scientific tour of Gdansk. If you enjoy scientific sites, good food and beer, be sure to visit this impressive Baltic port. You will not regret it!

|

- MY SCIENCE WALKS

- SHORT BIO

-

STELLARIUM RESOURCES

- Introduction

- Astronomy and the Odyssey

- Circumference of the Earth (Eratosthenes)

- Circumference of the Earth (Posidonius)

- Distance to the Sun (Aristarchus)

- Size of the Moon (Aristarchus)

- Distance to the Moon (Hipparchus)

- Lunar eclipse of Alexander the Great

- Journey of Pytheas

- Babylonian Cycles

- Direction to Mecca

- Great Conjunction of 1166

- Medieval supernovas

- Chinese pole star

- Sidereal day of Aryabhata

- NAVIGATING WITH THE STARS

- ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM

- BOOKS & COURSES

- TRAVEL BLOG

- Contact Me

RSS Feed

RSS Feed