|

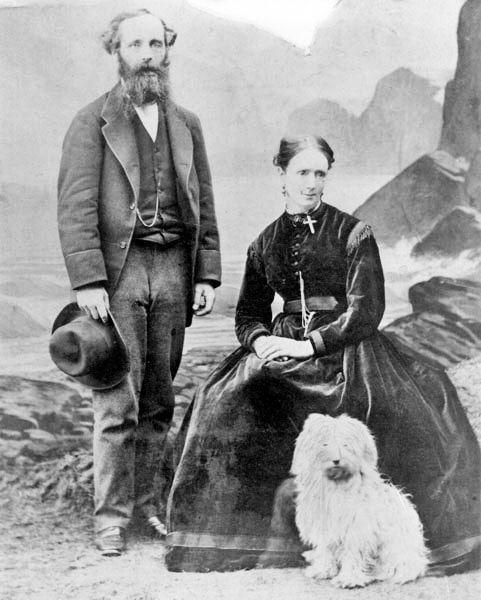

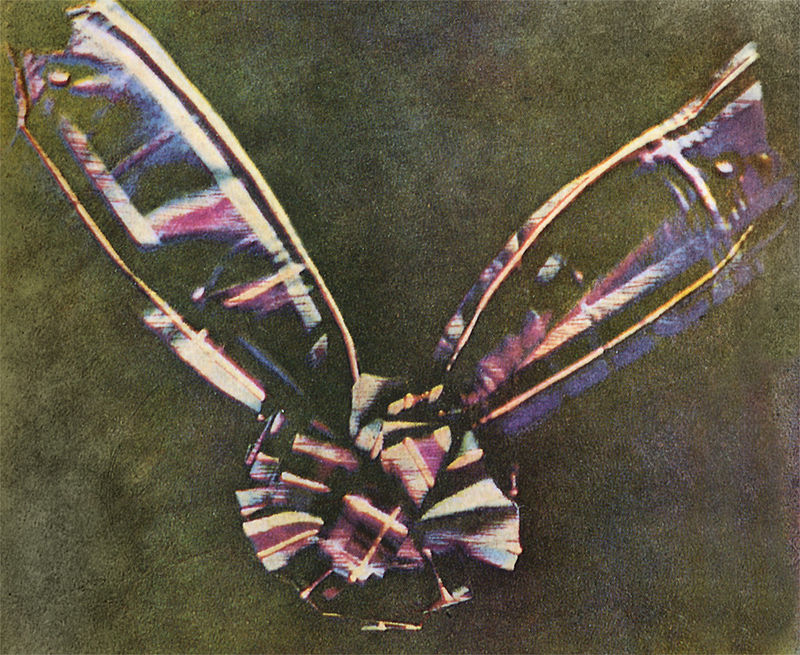

Edinburgh is the birthplace of one of the greatest scientists of all time and although many visitors will have heard of the likes of Newton and Einstein, few will be familiar with the name of James Clerk Maxwell. Most physicists, on the other hand, would rank Maxwell alongside the above mentioned giants of physics. In fact, there was no greater admirer of the man than Albert Einstein himself, who kept a portrait of the Scot in his office and who once remarked that: “One scientific epoch ended and another began with James Clerk Maxwell”. The young Maxwell at Cambridge James Clerk Maxwell was born in Edinburgh’s New Town, at 14 India Street, on the 13th of June 1831 and was brought up on the family estate at Glenlair, near Dumfries in southwest Scotland. When Maxwell returned to Edinburgh to start school and appeared at the Edinburgh Academy (still functioning today), his country boy appearance was the subject of mockery from his new classmates and he soon acquired the nickname “Dafty”. That changed when his academic capabilities started to show. Astonishingly, he wrote his first scientific paper when he was just 14. One of his father’s friends, Professor James Forbes read the paper to the Royal Society of Edinburgh, as James was too young to present it himself. In 1847 at the age of 16, he enrolled at Edinburgh University and when he was 18, he published another two papers which he was once again deemed too young to present at the Royal Society himself. In 1850 he moved to Cambridge University where he distinguished himself as Second Wrangler and joint winner of the prestigious Smith’s prize for his performance in mathematics. During his Cambridge years he was in frequent contact with many outstanding undergraduates who at times would visit his room seeking his mathematical advice. Maxwell with his wife Katherine and their dog In 1856, the year his father passed away, Maxwell became Professor of Physics at Marischal College, Aberdeen. Still only 25 years old, he was at least 15 years younger than most of his colleagues. Although busy with organising his teaching (which included weekly evening lectures to working men at the Aberdeen Mechanics’ Institute), he carried on with his scientific work that included the publication of a breakthrough paper on the theory of gases. His research on the stability of Saturn’s rings (a problem that had eluded scientists for 200 years), resulted in his being awarded the prestigious Adams prize, further enhancing his reputation. Aberdeen also brought him good fortune in his personal life as he got married to the daughter of the Principal, Katherine Mary Dewar, in 1858. In 1860 he left his native Scotland once again, this time appointed to the Chair of Natural Philosophy and Astronomy at London’s King’s College, where he carried out some of his most important scientific works. He was awarded the Rumford medal for his research on colour vision and in 1861 produced the world’s first ever colour photograph which he chose to be of a tartan ribbon, a tribute to his native country. He also continued to publish extensively on the behaviour of gases. It was, however, his work on electromagnetism that would eventually elevate him to the status of Einstein and Newton. First colour photograph What Maxwell did, in simple words (building on the work undertaken by scientists such as Michael Faraday), was to suggested that light, electricity and magnetism could all be explained in a single electromagnetic theory. His final paper on the subject, “A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field”, was written in 1864 and is considered one of the most important papers ever published in physics. Not only did it explain electromagnetism, but it also provided inspiration to 20th century scientists leading to the development of theories such as the theory of relativity and quantum theory. In 1865 Maxwell resigned the chair at King’s College and returned to Glenlair with his wife Katherine. He stayed there for 6 years producing research papers and books on topics such as heat theory and engineering. In 1871 he returned to Cambridge to become the first Cavendish Professor of Physics and was put in charge of the development of the Cavendish Laboratory, which eventually became one of the most important research hubs in the world. James Clerk Maxwell died at the young age of 48, in 1879. His remains were brought back to Scotland and buried beside those of his parents in the ruins of the old Kirk, at the village of Parton (close to Glenlair). Maxwell’s birthplace is a terraced house built for his father in 1820. The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation founded in 1977, acquired it in 1993. The original character of the house has, to a large extent, been preserved. Minor alterations have been made primarily for converting the former dining room into a small museum. The museum displays memorabilia such as portraits, manuscripts and books associated with Maxwell, his family and his scientific contemporaries. Maxwell's birthplace at 14, India Street It is possible to visit the house (admission free) and one hour tours are conducted every Tuesday. For more information on the site and how to organise a visit, check out the website: http://www.clerkmaxwellfoundation.org. A 15 minutes’ walk from his birthplace, at the eastern entrance of George Street, there is a statue of Maxwell together with his beloved dog Toby, a fitting tribute to the greatest scientist ever born in Scotland. A Charitable Trust has also been established to conserve and preserve the family home of Maxwell at Glenlair (a 2.5 hr drive from Edinburgh). A visitor centre has been set up and visits can be arranged through the Glenlair Trust website: http://www.glenlair.org.uk. Maxwell's statue in Edinburgh If you want to find more about James Maxwell and the fascinating scientific history of Edinburgh and Glasgow, check out the Scientific Secrets of Edinburgh and Glasgow here!

|

- MY SCIENCE WALKS

- SHORT BIO

-

STELLARIUM RESOURCES

- Introduction

- Astronomy and the Odyssey

- Circumference of the Earth (Eratosthenes)

- Circumference of the Earth (Posidonius)

- Distance to the Sun (Aristarchus)

- Size of the Moon (Aristarchus)

- Distance to the Moon (Hipparchus)

- Lunar eclipse of Alexander the Great

- Journey of Pytheas

- Babylonian Cycles

- Direction to Mecca

- Great Conjunction of 1166

- Medieval supernovas

- Chinese pole star

- Sidereal day of Aryabhata

- NAVIGATING WITH THE STARS

- ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM

- BOOKS & COURSES

- TRAVEL BLOG

- Contact Me

RSS Feed

RSS Feed