|

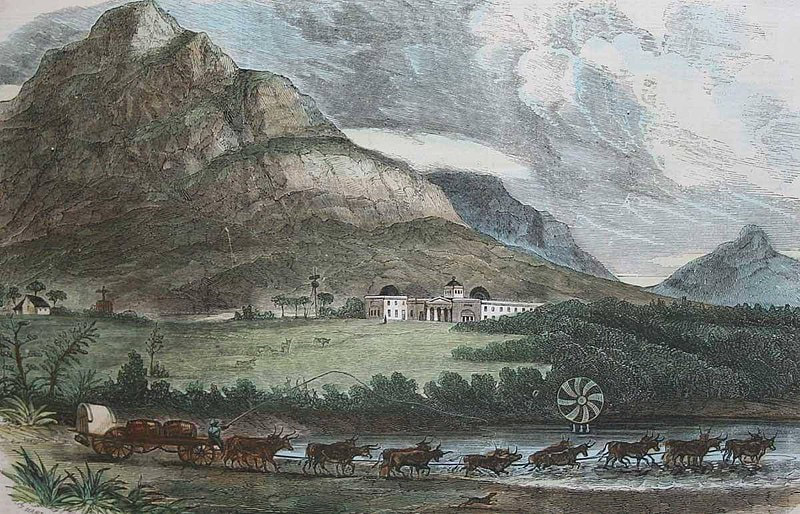

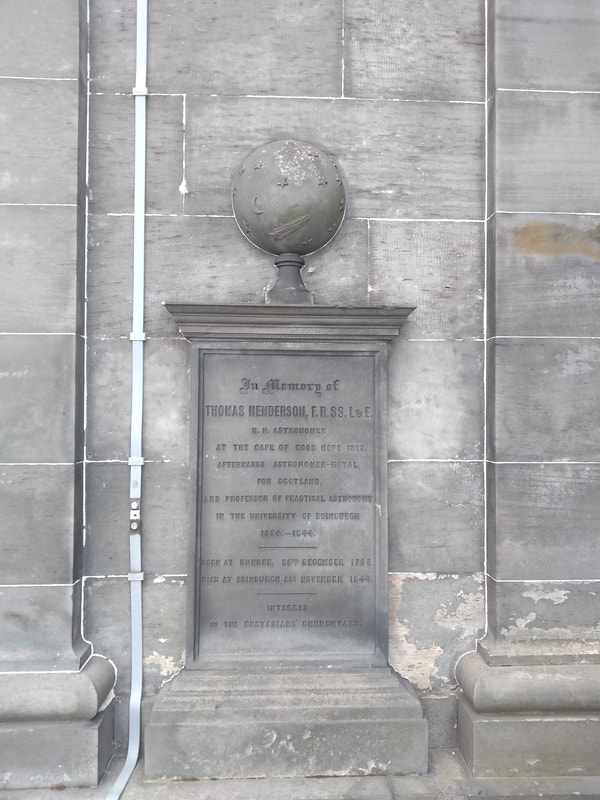

How many people, even those with a scientific interest, are aware that Edinburgh is associated with one of the holy grails of astronomy? Thomas Henderson's House, Hillhead Crescent, Edinburgh The story is one that begins many thousand miles from Edinburgh, at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa. It is where the Scottish astronomer, Thomas Henderson, was appointed H.M. Royal Astronomer in the year 1831. Born in Dundee in 1798, he began his career as a lawyer’s clerk, before his passion for astronomy eventually led to his appointment. Although complaining of the difficult working conditions (from defect telescopes, to having to check for snakes under his bed), he made a substantial number of astronomical observations during his time at the Cape. After just over a year, however, he decided he had endured enough of the “dismal swamp” as he called it, his frail health being affected by the local climate. His predecessor had died from scarlet fever and was actually buried in the observatory grounds, so Henderson returned to Scotland probably trying to avoid a similar fate. Portrait of Thomas Henderson During his last month in South Africa, intrigued by the observation made by another astronomer, Manuel Johnson based on the south Atlantic island of St Helena, that the star alpha Centauri (technically a star system) which is the closest to our solar system, exhibited a substantial change in its position relative to other stars, he focused his work on this discovery. What he was primarily interested in was the detection of a parallax for alpha Centauri, the apparent change in position of an object when viewed from different vantage points. As our planet moves around the sun, the view we get of a star changes ever so slightly during the year as it appears to move relative to its background. The fact that alpha Centauri seemed to exhibit a measurable movement, suggested that a parallax effect might be at play. Importantly, by obtaining the parallax of an object, it is possible to estimate its distance (the closer the object is to the observer, the greater the parallax). As stars are at an immense distance from us, their parallax is extremely small and is not detectable to the naked eye. Ever since antiquity, astronomers had been trying, without success, to detect this subtle effect. Nineteenth century telescopes however, had reached the technological level required for parallax detection and astronomers were caught up in a tantalising race to reach this holy grail of astronomy. The Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope Even so, for reasons that are still not entirely clear, Henderson apparently saw no urgency in further analysing his observations of alpha Centauri and instead applied himself to more routine tasks after returning to his native country. Had he possessed the confidence to formally publish his results, his claim to fame would have been much greater. The announcement from the German astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel that he had managed to measure the parallax and therefore the distance of another star, 61 Cyg, finally motivated Henderson to analyse his results in more detail in late 1838. In January 1839, more than six years after his observations had been made, he published his results which were read at a meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). His initial parallax estimations determined the distance of alpha Centauri to be at 3.25 light years (one light year being the distance travelled by light in a vacuum in one year) when in fact it is 4.37 light years. He later improved his estimate to 3.57 light years, after obtaining better quality results from his successor (and good friend) at Cape Town, astronomer Thomas Maclear. Thomas Henderson Commemoration Plaque, Calton Hill, Edinburgh Although the accuracy of the results may not be great by modern standards, Henderson had gauged the distance of a star, a feat of historical significance. Incredibly, he had achieved this without fully believing or realising it himself, and so came second to formally publishing a result. It is because of this that it was Bessel and not Henderson who was awarded the Gold Medal from the RAS and who is generally acknowledged as the winner of the scientific race. In fact, within just a few months, three astronomers had published their star parallax results (the third one being the German-Russian astronomer Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve). So important was the feat that when John Herschel, the president of the RAS, awarded the medal, he declared: “Gentlemen, I congratulate you and myself that we have lived to see the great and hitherto impassable barrier to our excursions into the sidereal universe—that barrier against which we have chafed so long and so vainly - almost simultaneously overleaped at three different points. It is the greatest and most glorious triumph which practical astronomy has ever witnessed”. So how is this fascinating story of science history connected to Edinburgh's Calton Hill that overlooks the eastern end of Princess Street (Edinburgh’s main shopping street)? After returning to Scotland Henderson was appointed the first ever Scottish Astronomer Royal and Professor of Astronomy at Edinburgh university. He worked at the Calton Hill observatory for ten years, recording over 60,000 observations of star positions. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1832, the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1834, and the Royal Society of London in 1840. Henderson died from heart disease at his home, in 1844. Two years before his death he met Bessel in Edinburgh in what he described as one of the highlights of his life. A plaque outside the main observatory building commemorates him and the house in which he spent his final years is also signposted at the foot of the hill. Although little known and difficult to imagine, a scientific quest which started in antiquity, was concluded in this very part of the city of Edinburgh. The Calton Hill Observatory The Calton Hill Observatory has many other stories that will certainly fascinate you. To learn more about those and about several other sites and aspects of the rich scientific history of Edinburgh & Glasgow, check out the Scientific Secrets of Edinburgh & Glasgow!

|

- MY SCIENCE WALKS

- SHORT BIO

-

STELLARIUM RESOURCES

- Introduction

- Astronomy and the Odyssey

- Circumference of the Earth (Eratosthenes)

- Circumference of the Earth (Posidonius)

- Distance to the Sun (Aristarchus)

- Size of the Moon (Aristarchus)

- Distance to the Moon (Hipparchus)

- Lunar eclipse of Alexander the Great

- Journey of Pytheas

- Babylonian Cycles

- Direction to Mecca

- Great Conjunction of 1166

- Medieval supernovas

- Chinese pole star

- Sidereal day of Aryabhata

- NAVIGATING WITH THE STARS

- ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM

- BOOKS & COURSES

- TRAVEL BLOG

- Contact Me

RSS Feed

RSS Feed